Tamir Hargana/ Mongolian Throat Singer/ World Music U of Kentucky 2018

471 views•Nov 5, 201830ShareSaveKeith Gilbertson 7.29K subscribers Tamir Hargana/ Mongolian Throat Singer/ World Music U of Kentucky 2018

Tamir Hargana/ Mongolian Throat Singer/ World Music U of Kentucky 2018

471 views•Nov 5, 201830ShareSaveKeith Gilbertson 7.29K subscribers Tamir Hargana/ Mongolian Throat Singer/ World Music U of Kentucky 2018

Tamir Hargana/ Mongolian Throat Singing/ U Kentucky / Nov2018

House of Voices — Mongolian Throat Singing by Tamir Hargana

203 views•Jan 14, 2020110ShareSaveHouse of Voices Calarts 1 subscriber In this workshop, Tamir Hargana (master throat singer from Inner Mongolia, China) will begin by demonstrating the main styles of throat singing (khöömii) from Mongolia and Tuva. He will explain the cultural significance of khöömii in Mongolian and Tuvan cultures and will also explain the acoustical phenomenon of how a single person can produce drone and overtones at the same time. He will then engage workshop participants in experimenting with vowel sounds, breath support, and “shaha” (the basic technique for building a khöömii sound in Mongolia) with time throughout for participants to ask questions.

Hugjiltu (3) at Rasmus Lyberth’s 60th birthday party, Odense, Denmark

1,213 views•Aug 23, 2011 14 0 Share Savecopenmiller 39 subscribers Amazing music! Inner Mongolian musician Hugjiltu performs at Greenlandic musician Rasmus Lyberth’s 60th birthday party in Rasmus’ backyard, August 20, 2011. Hugjiltu lives in Beijing, and performs with Ajinai Band (http://www.myspace.com/ajinaiband).

http://hdl.handle.net/10125/101902| File | Description | Size | Format | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D’Evelyn_Charlotte_r.pdf | Version for non-UH users. Copying/Printing is not permitted | 9.04 MB | Adobe PDF |

| D’Evelyn_Charlotte_uh.pdf | Version for UH users | 9.11 MB | Adobe PDF |

| Title: | Music between worlds : Mongol music and ethnicity in Inner Mongolia, China |

| Authors: | D’Evelyn, Charlotte Alexandra |

| Keywords: | Mongols |

| Date Issued: | May 2013 |

| Publisher: | [Honolulu] : [University of Hawaii at Manoa], [May 2013] |

| Abstract: | The Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (IMAR) of China is home to a diverse group of ethnic Mongols who live across the border from the nation of Mongolia, in a division that has existed for almost a century. As Inner Mongols have negotiated their position as ethnic minorities in China and a people between cultural worlds, they have used music to reconcile, and sometimes even celebrate, the complexities of their history and contemporary condition. In this dissertation, I argue that Inner Mongols’ contact with a variety of Mongol, Chinese, and Western musical styles has inspired them to take up creative and energetic musical expressions, particularly as they traverse shifting minority politics in China and determine how to represent themselves on national and international stages. The first part of this dissertation traces the work of four musical elites, two Mandarin-language grassland song composers and two reformers of the morin khuur horse-head fiddle, who have been formative in the staging of a unified, orthodox Mengguzu (Mongol ethnic group) representations for the national stage. I demonstrate how these musical leaders adeptly negotiated the communist system in China and became the voices and faces of their Mongols through their musical developments and reforms. The second part of this dissertation highlights new understandings of Mongolness that have emerged in the past decade. I explore Inner Mongol efforts to locate local heritage through the folk fiddle chor, on the one hand, and to forge links with the nation of Mongolia through morin khuur and khoomii styles, on the other. Through these two strategies–looking locally inward and transnationally outward–musicians have reconfigured themselves as Mongol peoples outside orthodox representations of previous decades. Through these case studies, I demonstrate that Mongol individuals in China have occupied a central role in national and transnational discussions about musical Mongolness, cultural development, purity and preservation, and the Mongol past (Humphrey 1992, Marsh 2009). By critically examining instrument reform efforts, compositional fusions, musical discourses, and stage performances in Inner Mongolia, I explore how Mongol individuals have used music as a means to pursue creative artistic careers and, moreover, as a way to creatively invoke and contest musical representations of their ethnicity over the past six decades |

| Description: | Ph.D. University of Hawaii at Manoa 2013. Includes bibliographical references. |

| URI: | http://hdl.handle.net/10125/101902 |

| Appears in Collections: | Ph.D. – Music |

Jump to navigation Jump to search

|

Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region

Nei Mongol Autonomous Region[1] |

|

|---|---|

| Name transcription(s) | |

| • Chinese | Simplified: 内蒙古自治区 Traditional: 內蒙古自治區 PRC Standard Mandarin: Nèi Měnggǔ Zìzhìqū ROC Standard Mandarin: Nèi Ménggǔ Zìzhìqū |

| • Abbreviation | NM Simplified: 内蒙 or 内蒙古[2] Traditional: 內蒙 or 內蒙古 PRC Standard Mandarin: Nèi Měng or Nèi Měnggǔ ROC Standard Mandarin: Nèi Méng or Nèi Ménggǔ |

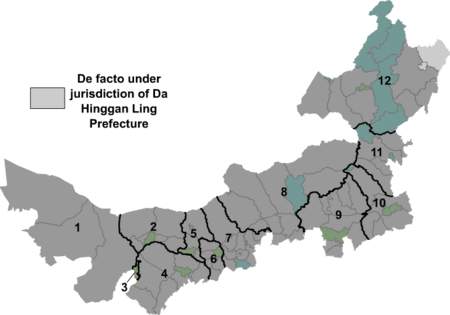

Map showing the location of Inner Mongolia

|

|

| Coordinates: 44°N 113°ECoordinates: 44°N 113°E | |

| Named for | From the Mongolian öbür monggol, where öbür means the front, sunny side of a barrier (a mountain, mountain range, lake, desert, clothes etc…) |

| Capital | Hohhot |

| Largest city | Baotou |

| Divisions | 12 prefectures, 101 counties, 1425 townships |

| Government | |

| • Secretary | Li Jiheng |

| • Chairwoman | Bu Xiaolin |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,183,000 km2 (457,000 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 3rd |

| Highest elevation

(Main Peak, Helan Mountains[4])

|

3,556 m (11,667 ft) |

| Population

(2010)[5]

|

|

| • Total | 24,706,321 |

| • Estimate

(31 December 2014)[6]

|

25,050,000 |

| • Rank | 23rd |

| • Density | 20.2/km2 (52/sq mi) |

| • Density rank | 28th |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic composition | Han – 79% Mongol – 17% Manchu – 2% Hui – 0.9% Daur – 0.3% |

| • Languages and dialects | Mandarin (official),[7] Mongolian (official), Oirat, Buryat, Dagur, Evenki, Jin |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-NM |

| GDP (2017 [8]) | CNY 1.61 trillion USD 238.50 billion (22nd) |

| – per capita | CNY 81,791 USD 12,156 (7th) |

| HDI (2017) | 0.771[9](high) (7th) |

| Website | http://www.nmg.gov.cn (Simplified Chinese) |

| Inner Mongolia | |||

Part of the Great Wall of China

|

|||

| Chinese name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 内蒙古 | ||

| Traditional Chinese | 內蒙古 | ||

| Hanyu Pinyin | PRC Standard Mandarin: Nèi Měnggǔ ROC Standard Mandarin: Nèi Ménggǔ |

||

| Literal meaning | Inner Mongolia | ||

|

|

|||

|

|||

| Mongolian name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Өвөр Монгол (Övör Mongol) |

||

| Mongolian script | ᠦᠪᠦᠷ ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ |

||

|

|

|||

|

|||

| Manchu name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Manchu script | ᡩᠣᡵᡤᡳ ᠮᠮᠣᠩᡤᠣ |

||

| Romanization | Dorgi monggo | ||

| Nei Mongol Autonomous Region | |||

| Chinese name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 内蒙古自治区 | ||

| Traditional Chinese | 內蒙古自治區 | ||

| Hanyu Pinyin | PRC Standard Mandarin: Nèi Měnggǔ Zìzhìqū ROC Standard Mandarin: Nèi Ménggǔ Zìzhìqū |

||

| Literal meaning | Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region | ||

|

|

|||

|

|||

| Mongolian name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Өвөр Монголын Өөртөө Засах Орон (Övör Mongolyn Öörtöö Zasakh Oron) |

||

| Mongolian script | ᠦᠪᠦᠷ ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠤᠨ ᠥᠪᠡᠷᠲᠡᠭᠡᠨ ᠵᠠᠰᠠᠬᠣ ᠣᠷᠣᠨ |

||

|

|

|||

|

Inner Mongolia or Nei Mongol (Mongolian: Mongolian script: ![]() Öbür Monggol, Mongolian Cyrillic: Өвөр Монгол[1] Övör Mongol /ɵwɵr mɔŋɢɔɮ/; simplified Chinese: 内蒙古; traditional Chinese: 內蒙古; pinyin: PRC Standard Mandarin: Nèi Měnggǔ, ROC Standard Mandarin: Nèi Ménggǔ), officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region or Nei Mongol Autonomous Region (NMAR), is a Mongolic autonomous region in Northern China. Its border includes most of the length of China’s border with Mongolia (Dornogovi, Sükhbaatar, Ömnögovi, Bayankhongor, Govi-Altai, Dornod Provinces). The rest of the Sino–Mongolian border coincides with part of the international border of the Xinjiang autonomous region and the entirety of the international border of Gansu province and a small section of China’s border with Russia (Zabaykalsky Krai).[a] Its capital is Hohhot; other major cities include Baotou, Chifeng, and Ordos.

Öbür Monggol, Mongolian Cyrillic: Өвөр Монгол[1] Övör Mongol /ɵwɵr mɔŋɢɔɮ/; simplified Chinese: 内蒙古; traditional Chinese: 內蒙古; pinyin: PRC Standard Mandarin: Nèi Měnggǔ, ROC Standard Mandarin: Nèi Ménggǔ), officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region or Nei Mongol Autonomous Region (NMAR), is a Mongolic autonomous region in Northern China. Its border includes most of the length of China’s border with Mongolia (Dornogovi, Sükhbaatar, Ömnögovi, Bayankhongor, Govi-Altai, Dornod Provinces). The rest of the Sino–Mongolian border coincides with part of the international border of the Xinjiang autonomous region and the entirety of the international border of Gansu province and a small section of China’s border with Russia (Zabaykalsky Krai).[a] Its capital is Hohhot; other major cities include Baotou, Chifeng, and Ordos.

The Autonomous Region was established in 1947, incorporating the areas of the former Republic of China provinces of Suiyuan, Chahar, Rehe, Liaobei and Xing’an, along with the northern parts of Gansu and Ningxia.

Its area makes it the third largest Chinese subdivision, constituting approximately 1,200,000 km2 (463,000 sq mi) and 12% of China’s total land area. It recorded a population of 24,706,321 in the 2010 census, accounting for 1.84% of Mainland China‘s total population. Inner Mongolia is the country’s 23rd most populous province-level division.[10] The majority of the population in the region are Han Chinese, with a sizeable titular Mongol minority. The official languages are Mandarin and Mongolian, the latter of which is written in the traditional Mongolian script, as opposed to the Mongolian Cyrillic alphabet, which is used in the state of Mongolia (formerly often described in the West as “Outer Mongolia“).

In Chinese, the region is known as “Inner Mongolia”, where the terms of “Inner/Outer” are derived from Manchu dorgi/tulergi (cf. Mongolian dotugadu/gadagadu). Inner Mongolia is distinct from Outer Mongolia, which was a term used by the Republic of China and previous governments to refer to what is now the independent state of Mongolia plus the Republic of Tuva in Russia. The term Inner 内 (Nei) referred to the Nei Fan 内藩 (Inner Tributary), i.e. those descendants of Genghis Khan who granted the title khan (king) in Ming and Qing dynasties and lived in part of southern part of Mongolia. In Mongolian, the region was called Dotugadu monggol during Qing rule and was renamed into Öbür Monggol in 1947, öbür meaning the southern side of a mountain, while the Chinese term Nei Menggu was retained.

Much of what is known about the history of Greater Mongolia, including Inner Mongolia, is known through Chinese chronicles and historians. Before the rise of the Mongols in the 13th century, what is now central and western Inner Mongolia, especially the Hetao region, alternated in control between Chinese agriculturalists in the south and Xiongnu, Xianbei, Khitan, Jurchen, Tujue, and nomadic Mongol of the north. The historical narrative of what is now Eastern Inner Mongolia mostly consists of alternations between different Tungusic and Mongol tribes, rather than the struggle between nomads and Chinese agriculturalists.

Slab Grave cultural monuments are found in northern, central and eastern Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, north-western China, southern, central-eastern and southern Baikal territory. Mongolian scholars prove that this culture related to the Proto-Mongols.[11]

During the Zhou dynasty, central and western Inner Mongolia (the Hetao region and surrounding areas) were inhabited by nomadic peoples such as the Loufan, Linhu, and Dí, while eastern Inner Mongolia was inhabited by the Donghu. During the Warring States period, King Wuling (340–295 BC) of the state of Zhao based in what is now Hebei and Shanxi provinces pursued an expansionist policy towards the region. After destroying the Dí state of Zhongshan in what is now Hebei province, he defeated the Linhu and Loufan and created the Yunzhong Commandery near modern Hohhot. King Wuling of Zhao also built a long wall stretching through the Hetao region. After Qin Shi Huang created the first unified Chinese empire in 221 BC, he sent the general Meng Tian to drive the Xiongnu from the region, and incorporated the old Zhao wall into the Qin dynasty Great Wall of China. He also maintained two commanderies in the region: Jiuyuan and Yunzhong and moved 30,000 households there to solidify the region. After the Qin dynasty collapsed in 206 BC, these efforts were abandoned.[12]

During the Western Han dynasty, Emperor Wu sent the general Wei Qing to reconquer the Hetao region from the Xiongnu in 127 BC. After the conquest, Emperor Wu continued the policy of building settlements in Hetao to defend against the Xiong-Nu. In that same year, he established the commanderies of Shuofang and Wuyuan in Hetao. At the same time, what is now eastern Inner Mongolia was controlled by the Xianbei, who would, later on, eclipse the Xiongnu in power and influence.

During the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 AD), Xiongnu who surrendered to the Han dynasty began to be settled in Hetao and intermingled with the Han immigrants in the area. Later on during the Western Jin dynasty, it was a Xiongnu noble from Hetao, Liu Yuan, who established the Han Zhao kingdom in the region, thereby beginning the Sixteen Kingdoms period that saw the disintegration of northern China under a variety of Han and non-Han (including Xiongnu and Xianbei) regimes.

The Sui dynasty (581–618) and Tang dynasty (618–907) re-established a unified Chinese empire, and like their predecessors, they conquered and settled people into Hetao, though once again these efforts were aborted when the Tang empire began to collapse. Hetao (along with the rest of what now consists Inner Mongolia) was then taken over by the Khitan Empire (Liao dynasty), founded by the Khitans, a nomadic people originally from what is now the southern part of Manchuria and eastern Inner Mongolia. They were followed by the Western Xia of the Tanguts, who took control of what is now the western part of Inner Mongolia (including western Hetao). The Khitans were later replaced by the Jurchens, precursors to the modern Manchus, who established the Jin dynasty over Manchuria and northern China.

After Genghis Khan unified the Mongol tribes in 1206 and founded the Mongol Empire, the Tangut Western Xia empire was ultimately conquered in 1227, and the Jurchen Jin dynasty fell in 1234. In 1271, Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan established the Yuan dynasty. Kublai Khan’s summer capital Shangdu (aka Xanadu) was located near present-day Dolonnor. During that time Ongud and Khunggirad peoples dominated the area of what is now Inner Mongolia. After the Yuan dynasty was overthrown by the Han-led Ming dynasty in 1368, the Ming captured parts of Inner Mongolia including Shangdu and Yingchang. The Ming rebuilt the Great Wall of China at its present location, which roughly follows the southern border of the modern Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (though it deviates significantly at the Hebei-Inner Mongolia border). The Ming established the Three Guards composed of the Mongols there. Soon after the Tumu incident in 1449, when the Oirat ruler Esen taishi captured the Chinese emperor, Mongols flooded south from Outer Mongolia to Inner Mongolia. Thus from then on until 1635, Inner Mongolia was the political and cultural center of the Mongols during the Northern Yuan dynasty.[13]

The eastern Mongol tribes near and in Manchuria, particularly the Khorchin and Southern Khalkha in today’s Inner Mongolia intermarried, formed alliances with, and fought against the Jurchen tribes until Nurhaci, the founder of the new Jin dynasty, consolidated his control over all groups in the area in 1593.[14] The Manchus gained far-reaching control of the Inner Mongolian tribes in 1635, when Ligden Khan‘s son surrendered the Chakhar Mongol tribes to the Manchus. The Manchus subsequently invaded Ming China in 1644, bringing it under the control of their newly established Qing dynasty. Under the Qing dynasty (1636–1912), Greater Mongolia was administered in a different way for each region:

The Inner Mongolian Chahar leader Ligdan Khan, a descendant of Genghis Khan, opposed and fought against the Qing until he died of smallpox in 1634. Thereafter, the Inner Mongols under his son Ejei Khan surrendered to the Qing and was given the title of Prince (親王; qīn wáng), and Inner Mongolian nobility became closely tied to the Qing royal family and intermarried with them extensively. Ejei Khan died in 1661 and was succeeded by his brother Abunai. After Abunai showed disaffection with Manchu Qing rule, he was placed under house arrest in 1669 in Shenyang and the Kangxi Emperor gave his title to his son Borni. Abunai then bid his time and then he and his brother Lubuzung revolted against the Qing in 1675 during the Revolt of the Three Feudatories, with 3,000 Chahar Mongol followers joining in on the revolt. The revolt was put down within two months, the Qing then crushed the rebels in a battle on April 20, 1675, killing Abunai and all his followers. Their title was abolished, all Chahar Mongol royal males were executed even if they were born to Manchu Qing princesses, and all Chahar Mongol royal females were sold into slavery except the Manchu Qing princesses. The Chahar Mongols were then put under the direct control of the Qing Emperor, unlike the other Inner Mongol leagues which maintained their autonomy.

Despite officially prohibiting Han Chinese settlement on the Manchu and Mongol lands, by the 18th century the Qing decided to settle Han refugees from northern China who were suffering from famine, floods, and drought into Manchuria and Inner Mongolia so that Han Chinese farmed 500,000 hectares in Manchuria and tens of thousands of hectares in Inner Mongolia by the 1780s.[15]

Ordinary Mongols were not allowed to travel outside their own leagues. Mongols were forbidden by the Qing from crossing the borders of their banners, even into other Mongol Banners and from crossing into neidi (the Han Chinese 18 provinces) and were given serious punishments if they did in order to keep the Mongols divided against each other to benefit the Qing.[16] Mongol pilgrims wanting to leave their banner’s borders for religious reasons such as pilgrimage had to apply for passports to give them permission.[17]

During the eighteenth century, growing numbers of Han Chinese settlers had illegally begun to move into the Inner Mongolian steppe. By 1791 there had been so many Han Chinese settlers in the Front Gorlos Banner that the jasak had petitioned the Qing government to legalize the status of the peasants who had already settled there.[18]

During the nineteenth century, the Manchus were becoming increasingly sinicized and faced with the Russian threat, they began to encourage Han Chinese farmers to settle in both Mongolia and Manchuria. This policy was followed by subsequent governments. The railroads that were being built in these regions were especially useful to the Han Chinese settlers. Land was either sold by Mongol Princes, or leased to Han Chinese farmers, or simply taken away from the nomads and given to Han Chinese farmers.

A group of Han Chinese during the Qing dynasty called “Mongol followers” immigrated to Inner Mongolia who worked as servants for Mongols and Mongol princes and married Mongol women. Their descendants continued to marry Mongol women and changed their ethnicity to Mongol as they assimilated into the Mongol people, an example of this were the ancestors of Li Shouxin. They distinguished themselves apart from “true Mongols” 真蒙古.[19][20][21]

|

|

The neutrality of this section is disputed. (March 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Outer Mongolia gained independence from the Qing dynasty in 1911, when the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu of the Khalkha was declared the Bogd Khan of Mongolia. Although almost all banners of Inner Mongolia recognized the Bogd Khan as the supreme ruler of Mongols, the internal strife within the region prevented a full reunification. The Mongol rebellions in Inner Mongolia were counterbalanced by princes who hoped to see a restored Qing dynasty in Manchuria and Mongolia, as they considered the theocratic rule of the Bogd Khan would be against their modernizing objectives for Mongolia.[22] Eventually, the newly formed Republic of China promised a new nation of five races (Han, Manchu, Mongol, Tibetan and Uyghur),[23] and suppressed the Mongol rebellions in the area,[24][25] forcing the Inner Mongolian princes to recognize the Republic of China.

The Republic of China reorganized Inner Mongolia into provinces:

Some Republic of China maps still show this structure.

The history of Inner Mongolia during the Second World War is complicated, with Japanese invasion and different kinds of resistance movements. In 1931, Manchuria came under the control of the Japanese puppet state Manchukuo, taking some Mongol areas in the Manchurian provinces (i.e. Hulunbuir and Jirim leagues) along. Rehe was also incorporated into Manchukuo in 1933, taking Juu Uda and Josutu leagues along with it. These areas were occupied by Manchukuo until the end of World War II in 1945.

In 1937, the Empire of Japan openly and fully invaded Republic of China by war. On December 8, 1937, Mongolian Prince Demchugdongrub (also known as “De Wang”) declared an independence of the remaining parts of Inner Mongolia (i.e. the Suiyuan and Chahar provinces) as Mengjiang, and signed an agreements with Manchukuo and Japan. Its capital was established at Zhangbei (now in Hebei province), with the Japanese puppet government’s control extending as far west as the Hohhot region. The Japanese advanced was defeated by Hui Muslim General Ma Hongbin at the Battle of West Suiyuan and Battle of Wuyuan. After 1945, Inner Mongolia has remained part of China.

The Mongol Ulanhu fought against the Japanese.

Ethnic Mongolian guerilla units were created by the Kuomintang Nationalists to fight against the Japanese during the war in the late 30s and early 40s. These Mongol militias were created by the Ejine and Alashaa based commissioner’s offices created by the Kuomintang.[26][27] Prince Demchugdongrob’s Mongols were targeted by Kuomintang Mongols to defect to the Republic of China. The Nationalists recruited 1,700 ethnic minority fighters in Inner Mongolia and created war zones in the Tumet Banner, Ulanchab League, and Ordos Yekejuu League.[26][28]

The Communist movement gradually gained momentum as part of the Third Communist International in Inner Mongolia during the Japanese period. By the end of WWII, the Inner Mongolian faction of the ComIntern had a functional militia and actively opposed the attempts at independence by De Wang’s Chinggisid princes on the grounds of fighting feudalism. Following the end of World War II, the Chinese Communists gained control of Manchuria as well as the Inner Mongolian Communists with decisive Soviet support and established the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in 1947. The Comintern army was absorbed into the People’s Liberation Army. Initially, the autonomous region included just the Hulunbuir region. Over the next decade, as the communists established the People’s Republic of China and consolidated control over mainland China, Inner Mongolia was expanded westwards to include five of the six original leagues (except Josutu League, which remains in Liaoning province), the northern part of the Chahar region, by then a league as well (southern Chahar remains in Hebei province), the Hetao region, and the Alashan and Ejine banners. Eventually, near all areas with sizeable Mongol populations were incorporated into the region, giving present-day Inner Mongolia its elongated shape. The leader of Inner Mongolia during that time, as both regional CPC secretary and head of regional government, was Ulanhu.

During the Cultural Revolution, the administration of Ulanhu was purged, and a wave of repressions was initiated against the Mongol population of the autonomous region.[29] In 1969 much of Inner Mongolia was distributed among surrounding provinces, with Hulunbuir divided between Heilongjiang and Jilin, Jirim going to Jilin, Juu Uda to Liaoning, and the Alashan and Ejine region divided among Gansu and Ningxia. This was reversed in 1979.

Inner Mongolia has seen considerable development since Deng Xiaoping instituted Chinese economic reform in 1978. For about ten years since 2000, Inner Mongolia’s GDP growth has been the highest in the country, (along with Guangdong) largely owing to the success of natural resource industries in the region. GDP growth has continually been over 10%, even 15% and connections with the Wolf Economy to the north has helped development. However, growth has come at a cost with huge amounts of pollution and degradation to the grasslands.[30] Attempts to attract ethnic Chinese to migrate from other regions, as well as urbanise those rural nomads and peasants has led to huge amounts of corruption and waste in public spending, such as Ordos City.[31][32] Acute uneven wealth distribution has further exacerbated ethnic tensions, many indigenous Mongolians feeling they are increasingly marginalised in their own homeland, leading to riots in 2011 and 2013.[33][34]

Officially Inner Mongolia is classified as one of the provincial-level divisions of North China, but its great stretch means that parts of it belong to Northeast China and Northwest China as well. It borders eight provincial-level divisions in all three of the aforementioned regions (Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Hebei, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Ningxia, and Gansu), tying with Shaanxi for the greatest number of bordering provincial-level divisions. Most of its international border is with Mongolia,[b] which, in Chinese, is sometimes called “Outer Mongolia“, while a small portion is with Russia’s Zabaykalsky Krai.

Inner Mongolia largely consists of the northern side of the North China Craton, a tilted and sedimented Precambrian block. In the extreme southwest is the edge of the Tibetan Plateau where the autonomous region’s highest peak, Main Peak in the Helan Mountains reaches 3,556 metres (11,670 ft), and is still being pushed up today in short bursts.[4] Most of Inner Mongolia is a plateau averaging around 1,200 metres (3,940 ft) in altitude and covered by extensive loess and sand deposits. The northern part consists of the Mesozoic era Khingan Mountains, and is owing to the cooler climate more forested, chiefly with Manchurian elm, ash, birch, Mongolian oak and a number of pine and spruce species. Where discontinuous permafrost is present north of Hailar District, forests are almost exclusively coniferous. In the south, the natural vegetation is grassland in the east and very sparse in the arid west, and grazing is the dominant economic activity.

Owing to the ancient, weathered rocks lying under its deep sedimentary cover, Inner Mongolia is a major mining district, possessing large reserves of coal, iron ore and rare-earth minerals, which have made it a major industrial region today.

Due to its elongated shape, Inner Mongolia has a four-season monsoon climate with regional variations. The winters in Inner Mongolia are very long, cold, and dry with frequent blizzards, though snowfall is so light that Inner Mongolia has no modern glaciers[4] even on the highest Helan peaks. The spring is short, mild and arid, with large, dangerous sandstorms, whilst the summer is very warm to hot and relatively humid except in the west where it remains dry. Autumn is brief and sees a steady cooling, with temperatures below 0 °C (32 °F) reached in October in the north and November in the south.

Officially, most of Inner Mongolia is classified as either a cold arid or steppe regime (Köppen BWk, BSk, respectively). The small portion besides these are classified as humid continental (Köppen Dwb) in the northeast, or subarctic (Köppen Dwc) in the far north near Hulunbuir.[35]

| City | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baotou | 29.6/17.1 | 85.3/62.8 | –4.1/–16.8 | 24.7/1.8 |

| Bayannur | 30.7/17.9 | 87.3/64.2 | –3.3/–15.1 | 26.1/4.8 |

| Hohhot | 28.5/16.4 | 83.3/61.5 | –5/–16.9 | 23/1.6 |

| Ordos | 26.7/15.8 | 80.1/60.4 | –4.8/–14.7 | 23.4/5.5 |

| Ulanqab | 25.4/13.6 | 77.7/56.5 | –6.1/–18.5 | 21/–1.3 |

Inner Mongolia is divided into twelve prefecture-level divisions. Until the late 1990s, most of Inner Mongolia’s prefectural regions were known as Leagues (Chinese: 盟), a usage retained from Mongol divisions of the Qing dynasty. Similarly, county-level divisions are often known as Banners (Chinese: 旗). Since the 1990s, numerous Leagues have converted into prefecture-level cities, although Banners remain. The restructuring led to the conversion of primate cities in most leagues to convert to districts administratively (i.e.: Hailar, Jining and Dongsheng). Some newly founded prefecture-level cities have chosen to retain the original name of League (i.e.: Hulunbuir, Bayannur and Ulanqab), some have adopted the Chinese name of their primate city (Chifeng, Tongliao), and one League (Yekejuu) simply renamed itself Ordos. Despite these recent administrative changes, there is no indication that the Alxa, Hinggan, and Xilingol Leagues will convert to prefecture-level cities in the near future.

| Administrative divisions of Inner Mongolia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Prefecture-level city district areas County-level cities Prefecture-level city district areas County-level cities |

|||||||||||||

| № | Division code[36] | Division | Area in km2[37] | Population 2010[38] | Seat | Divisions[39] | |||||||

| Districts | Counties Banners | Aut. banners | CL cities | ||||||||||

| 150000 | Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region | 1183000.00 | 24,706,321 | Hohhot city | 23 | 66 | 3 | 11 | |||||

| 6 | 150100 | Hohhot city | 17186.10 | 2,866,615 | Xincheng District | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| 5 | 150200 | Baotou city | 27768.00 | 2,650,364 | Jiuyuan District | 6 | 3 | ||||||

| 3 | 150300 | Wuhai city | 1754.00 | 532,902 | Haibowan District | 3 | |||||||

| 9 | 150400 | Chifeng city | 90021.00 | 4,341,245 | Songshan District | 3 | 9 | ||||||

| 10 | 150500 | Tongliao city | 59535.00 | 3,139,153 | Horqin District | 1 | 6 | 1 | |||||

| 4 | 150600 | Ordos city | 86881.61 | 1,940,653 | Hia’bagx District | 2 | 7 | ||||||

| 12 | 150700 | Hulunbuir city | 254003.79 | 2,549,278 | Hailar District | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 | ||||

| 2 | 150800 | Bayannur city | 65755.47 | 1,669,915 | Linhe District | 1 | 6 | ||||||

| 7 | 150900 | Ulanqab city | 54447.72 | 2,143,590 | Jining District | 1 | 9 | 1 | |||||

| 11 | 152200 | Hinggan League | 59806.00 | 1,613,250 | Ulanhot city | 4 | 2 | ||||||

| 8 | 152500 | Xilingol League | 202580.00 | 1,028,022 | Xilinhot city | 10 | 2 | ||||||

| 1 | 152900 | Alxa League | 267574.00 | 231,334 | Alxa Left Banner | 3 | |||||||

| Administrative divisions in Mongolian, Chinese, and varieties of romanizations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Mongolian | SASM/GNC Mongolian Pinyin | Mongolian Transcription | Chinese | Pinyin |

The twelve prefecture-level divisions of Inner Mongolia are subdivided into 102 county-level divisions, including 22 districts, 11 county-level cities, 17 counties, 49 banners, and 3 autonomous banners. Those are in turn divided into 1425 township-level divisions, including 532 towns, 407 townships, 277 sumu, eighteen ethnic townships, one ethnic sumu, and 190 subdistricts. At the end of 2017, the total population of Inner-Mongolia is 25.29 million.[1]

| Population by urban areas of prefecture & county cities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | City | Urban area[40] | District area[40] | City proper[40] | Census date |

| 1 | Baotou | 1,900,373 | 2,096,851 | 2,650,364 | 2010-11-01 |

| 2 | Hohhot | 1,497,110 | 1,980,774 | 2,866,615 | 2010-11-01 |

| 3 | Chifeng | 902,285 | 1,333,526 | 4,341,245 | 2010-11-01 |

| 4 | Tongliao | 540,338 | 898,895 | 3,139,153 | 2010-11-01 |

| 5 | Ordos[i] | 510,242 | 582,544 | 1,940,653 | 2010-11-01 |

| 6 | Wuhai | 502,704 | 532,902 | 532,902 | 2010-11-01 |

| 7 | Bayannur | 354,507 | 541,721 | 1,669,915 | 2010-11-01 |

| 8 | Yakeshi | 338,275 | 352,173 | see Hulunbuir | 2010-11-01 |

| 9 | Hulunbuir[ii] | 327,384 | 344,934 | 2,549,252 | 2010-11-01 |

| (9) | Hulunbuir (new district)[ii] | 99,960 | 99,960 | see Hulunbuir | 2010-11-01 |

| 10 | Ulanqab | 319,723 | 356,135 | 2,143,590 | 2010-11-01 |

| 11 | Ulanhot | 276,406 | 327,081 | part of Hinggan League | 2010-11-01 |

| 12 | Xilinhot | 214,382 | 245,886 | part of Xilingol League | 2010-11-01 |

| 13 | Zalantun | 167,493 | 366,323 | see Hulunbuir | 2010-11-01 |

| 14 | Manzhouli | 148,460 | 149,512 | see Hulunbuir | 2010-11-01 |

| 15 | Fengzhen | 123,811 | 245,608 | see Ulanqab | 2010-11-01 |

| 16 | Holingol | 101,496 | 102,214 | see Tongliao | 2010-11-01 |

| 17 | Genhe | 89,194 | 110,438 | see Hulunbuir | 2010-11-01 |

| 18 | Erenhot | 71,455 | 74,179 | part of Xilingol League | 2010-11-01 |

| 19 | Arxan | 55,770 | 68,311 | part of Hinggan League | 2010-11-01 |

| 20 | Ergun | 55,076 | 76,667 | see Hulunbuir | 2010-11-01 |

Farming of crops such as wheat takes precedence along the river valleys. In the more arid grasslands, herding of goats, sheep and so on is a traditional method of subsistence. Forestry and hunting are somewhat important in the Greater Khingan ranges in the east. Reindeer herding is carried out by Evenks in the Evenk Autonomous Banner. More recently, growing grapes and winemaking have become an economic factor in the Wuhai area.

Inner Mongolia has an abundance of resources especially coal, cashmere, natural gas, rare-earth elements, and has more deposits of naturally occurring niobium, zirconium and beryllium than any other province-level region in China. However, in the past, the exploitation and utilisation of resources were rather inefficient, which resulted in poor returns from rich resources. Inner Mongolia is also an important coal production base, with more than a quarter of the world’s coal reserves located in the province.[41] It plans to double annual coal output by 2010 (from the 2005 volume of 260 million tons) to 500 million tons of coal a year.[42]

Industry in Inner Mongolia has grown up mainly around coal, power generation, forestry-related industries, and related industries. Inner Mongolia now encourages six competitive industries: energy, chemicals, metallurgy, equipment manufacturing, processing of farm (including dairy) produce, and high technology. Well-known Inner Mongolian enterprises include companies such as ERDOS, Yili, and Mengniu.

The nominal GDP of Inner Mongolia in 2015 was 1.8 trillion yuan (US$272.1 billion), with an average annual increase of 10% from the period 2010-2015. Its per capita GDP reached US$11,500 in 2015, ranking No.4th among all the 31 provinces of China, only after Shanghai, Beijing and Tianjin.[43]

As with much of China, economic growth has led to a boom in construction, including new commercial development and large apartment complexes.

In addition to its large reserves of natural resources, Inner Mongolia also has the largest usable wind power capacity in China[41] thanks to strong winds which develop in the province’s grasslands. Some private companies have set up wind parks in parts of Inner Mongolia such as Bailingmiao, Hutengliang and Zhouzi.

Hohhot Export Processing Zone was established on June 21, 2002, by the State Council, which is located in the west of the Hohhot, with a planning area of 2.2 km2 (0.85 sq mi). Industries encouraged in the export processing zone include Electronics Assembly & Manufacturing, Telecommunications Equipment, Garment and Textiles Production, Trading and Distribution, Biotechnology/Pharmaceuticals, Food/Beverage Processing, Instruments & Industrial Equipment Production, Medical Equipment and Supplies, Shipping/Warehousing/Logistics, Heavy Industry.[45]

Under the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, articles 112-122, autonomous regions have limited autonomy in both the political and economic arena. Autonomous regions have more discretion in administering economic policy in the region in accordance with national guidelines. Structurally, the Chairman—who legally must be an ethnic minority and is usually ethnic Mongolian—is always kept in check by the Communist Party Regional Committee Secretary, who is usually from a different part of China (to reduce corruption) and Han Chinese. As of August 2016, the current party secretary is Li Jiheng. The Inner Mongolian government and its subsidiaries follow roughly the same structure as that of a Chinese province. With regards to economic policy, as a part of increased federalism characteristics in China, Inner Mongolia has become more independent in implementing its own economic roadmap.

The position of Chairman of Inner Mongolia alternates between Khorchin Mongols in the east and the Tumed Mongols in the west. Since the end of the Cultural Revolution, this convention has not been broken. The family of Ulanhu has retained influence in regional politics ever since the founding the People’s Republic. His son Buhe and granddaughter Bu Xiaolin both served as Chairman of the region.

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1954[46] | 6,100,104 | — |

| 1964[47] | 12,348,638 | +7.31% |

| 1982[48] | 19,274,279 | +2.50% |

| 1990[49] | 21,456,798 | +1.35% |

| 2000[50] | 23,323,347 | +0.84% |

| 2010[5] | 24,706,321 | +0.58% |

| Established in 1947 from dissolution of Xing’an Province, Qahar Province, parts of Rehe Province, and Suiyuan Province; parts of Ningxia Province were incorporated into Inner Mongolia AR. | ||

When the autonomous region was established in 1947, Han Chinese comprised 83.6% of the population, while the Mongols comprised 14.8% of the population.[51] By 2010, the percentage of Han Chinese had dropped to 79.5%. While the Hetao region along the Yellow River has always alternated between farmers from the south and nomads from the north, the most recent wave of Han Chinese migration began in the early 18th century with encouragement from the Qing dynasty, and continued into the 20th century. Han Chinese live mostly in the Hetao region as well as various population centres in central and eastern Inner Mongolia. Over 70% of Mongols are concentrated in less than 18% of Inner Mongolia’s territory (Hinggan League, and the prefectures of Tongliao and Chifeng).

Mongols are the second largest ethnic group, comprising 17.11% of the population as of the 2010 census.[52] They include many diverse Mongolian-speaking groups; groups such as the Buryats and the Oirats are also officially considered to be Mongols in China. In addition to the Manchus, other Tungusic ethnic groups, the Oroqen, and the Evenks also populate parts of northeastern Inner Mongolia.

Many of the traditionally nomadic Mongols have settled in permanent homes as their pastoral economy was collectivized during the Mao Era, and some have taken jobs in cities as migrant labourers; however, some Mongols continue in their nomadic tradition. In practice, highly educated Mongols tend to migrate to big urban centers after which they become essentially indistinct with ethnic Han Chinese populations.

Inter-marriage between Mongol and non-Mongol populations is very common, particularly in areas where Mongols are in regular contact with other groups. There was little cultural stigma within Mongol families for marrying outside the ethnic group, and in urban centers in particular, Mongol men and women married non-Mongols at relatively similar rates. The rates of intermarriage stands in very sharp contrast to ethnic Tibetans and Uyghurs in their respective autonomous regions. By the 1980s, for instance, in the former Jirim League, nearly 40% of marriages with at least one Mongol spouse was a mixed Mongol-Han Chinese marriage.[53] However, anecdotal reports have also demonstrated an increase in Mongol-female, Han Chinese-male pairings in which the woman is of a rural background, ostensibly shutting rural Mongol males from the marriage market as the sex ratio in China becomes more skewed with a much higher proportion of men.[54]

There is also a significant number of Hui and Koreans.

| Ethnicity | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Han | 19,650,687 | 79.54% |

| Mongol | 4,226,093 | 17.11% |

| Hui | 452,765 | 1.83% |

| Daur | 121,483 | 0.90% |

| Evenks | 26,139 | 0.11% |

| Oroqen people | 8,464 | 0.07% |

| Year | Population | Han Chinese | Mongol | Manchu | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953[56] | 6,100,104 | 5,119,928 | 83.9% | 888,235 | 14.6% | 18,354 | 0.3% |

| 1964[56] | 12,348,638 | 10,743,456 | 87.0% | 1,384,535 | 11.2% | 50,960 | 0.4% |

| 1982[56] | 19,274,281 | 16,277,616 | 84.4% | 2,489,378 | 12.9% | 237,149 | 1.2% |

| 1990[57] | 21,456,500 | 17,290,000 | 80.6% | 3,379,700 | 15.8% | ||

| 2000[58] | 23,323,347 | 18,465,586 | 79.2% | 3,995,349 | 17.1% | 499,911 | 2.3% |

| 2010[59] | 24,706,321 | 19,650,687 | 79.5% | 4,226,093 | 17.1% | 452,765 | 1.83% |

| Name of banner | Mongol population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Horqin Right Middle Banner, Hinggan (2009) | 222,410 | 84.1% |

| New Barag Right Banner, Hulunbuir (2009) | 28,369 | 82.2% |

| Horqin Left Back Banner, Tongliao | 284,000 | 75% |

| New Barag Left Banner, Hulunbuir (2009) | 31,531 | 74.9% |

| Horqin Left Middle Banner, Tongliao | 395,000 | 73.5% |

| East Ujimqin Banner, Xilingol (2009) | 43,394 | 72.5% |

| West Ujimqin Banner, Xilingol | 57,000 | 65% |

| Sonid Left Banner, Xilingol (2006) | 20,987 | 62.6% |

| Bordered Yellow Banner, Xilingol | 19,000 | 62% |

| Hure Banner, Tongliao | 93,000 | 56% |

| Jarud Banner, Tongliao | 144,000 | 48% |

| Horqin Right Front Banner, Hinggan | 162,000 | 45% |

| Old Barag Banner, Hulunbuir (2006) | 25,903 | 43.6% |

| Jalaid Banner, Hinggan | 158,000 | 39% |

| Ar Khorchin Banner, Chifeng (2002) | 108,000 | 36.6% |

Population numbers exclude members of the People’s Liberation Army in active service based in Inner Mongolia.

Alongside Chinese, Mongolian is the official provincial language of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, where there are at least 4.1 million ethnic Mongols.[62] Across the whole of China, the language is spoken by roughly half of the country’s 5.8 million ethnic Mongols (2005 estimate)[63] However, the exact number of Mongolian speakers in China is unknown, as there is no data available on the language proficiency of that country’s citizens. The use of Mongolian in China, specifically in Inner Mongolia, has witnessed periods of decline and revival over the last few hundred years. The language experienced a decline during the late Qing period, a revival between 1947 and 1965, a second decline between 1966 and 1976, a second revival between 1977 and 1992, and a third decline between 1995 and 2012.[64] However, in spite of the decline of the Mongolian language in some of Inner Mongolia’s urban areas and educational spheres, the ethnic identity of the urbanized Chinese-speaking Mongols is most likely going to survive due to the presence of urban ethnic communities.[65] The multilingual situation in Inner Mongolia does not appear to obstruct efforts by ethnic Mongols to preserve their language.[66][67] Although an unknown number of Mongols in China, such as the Tumets, may have completely or partially lost the ability to speak their language, they are still registered as ethnic Mongols and continue to identify themselves as ethnic Mongols.[63][68] The children of inter-ethnic Mongol-Chinese marriages also claim to be and are registered as ethnic Mongols.[69]

By law, all street signs, commercial outlets, and government documents must be bilingual, written in both Mongolian and Chinese. There are three Mongolian TV channels in the Inner Mongolia Satellite TV network. In public transportation, all announcements are to be bilingual.

Mongols in Inner Mongolia speak Mongolian dialects such as Chakhar, Xilingol, Baarin, Khorchin and Kharchin Mongolian and, depending on definition and analysis, further dialects[70] or closely related independent Central Mongolic languages[71] such as Ordos, Khamnigan, Barghu Buryat and the arguably Oirat dialect Alasha. The standard pronunciation of Mongolian in China is based on the Chakhar dialect of the Plain Blue Banner, located in central Inner Mongolia, while the grammar is based on all Southern Mongolian dialects.[72] This is different from the Mongolian state, where the standard pronunciation is based on the closely related Khalkha dialect. There are a number of independent languages spoken in Hulunbuir such as the somewhat more distant Mongolic language Dagur and the Tungusic language Evenki. Officially, even the Evenki dialect Oroqin is considered a language.[73]

The Han Chinese of Inner Mongolia speak a variety of dialects, depending on the region. Those in the eastern parts tend to speak Northeastern Mandarin, which belongs to the Mandarin group of dialects; those in the central parts, such as the Yellow River valley, speak varieties of Jin, another subdivision of Chinese, due to its proximity to other Jin-speaking areas in China such as the Shanxi province. Cities such as Hohhot and Baotou both have their unique brand of Jin Chinese such as the Zhangjiakou–Hohhot dialect which are sometimes incomprehensible with dialects spoken in northeastern regions such as Hailar.

The vast grasslands have long symbolised Inner Mongolia. Mongolian art often depicts the grassland in an uplifting fashion and emphasizes Mongolian nomadic traditions. The Mongols of Inner Mongolia still practice their traditional arts. Inner Mongolian cuisine has Mongol roots and consists of dairy-related products and hand-held lamb (手扒肉). In recent years, franchises based on Hot pot have appeared in Inner Mongolia, the best known of which is Xiaofeiyang. Notable Inner Mongolian commercial brand names include Mengniu and Yili, both of which began as dairy product and ice cream producers.

Among the Han Chinese of Inner Mongolia, Jinju (晋剧) or Shanxi Opera is a popular traditional form of entertainment. See also: Shanxi. A popular career in Inner Mongolia is circus acrobatics. The internationally known Inner Mongolia Acrobatic Troupe travels and performs with the renowned Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey Circus.

According to a survey held in 2004 by the Minzu University of China, about 80% of the population of the region practice the worship of Heaven (that is named Tian in the Chinese tradition and Tenger in the Mongolian tradition) and of ovoo/aobao.[74]

Official statistics report that 12.1% of the population (3 million people) are members of Tibetan Buddhist groups.[75] According to the Chinese Spiritual Life Survey of 2007 and the Chinese General Social Survey of 2009, Christianity is the religious identity of 2% of the population of the region; and Chinese ancestral religion the professed belonging of 2.36%,[76] while a demographic analysis of the year 2010 reported that Muslims comprise the 0.91%.[77]

The cult of Genghis Khan, present in the form of various Genghis Khan temples, is a tradition of Mongolian shamanism, in which he is considered a cultural hero and divine ancestor, an embodiment of the Tenger (Heaven, God of Heaven).[78] His worship in special temples, greatly developed in Inner Mongolia since the 1980s, is also shared by the Han Chinese, claiming his spirit as the founding principle of the Yuan dynasty.[79]

Tibetan Buddhism (Mongolian Buddhism, locally also known as “Yellow Buddhism”) is the dominant form of Buddhism in Inner Mongolia, also practiced by many Han Chinese. Another form of Buddhism, practiced by the Chinese, are the schools of Chinese Buddhism.

In the capital city Hohhot:

Elsewhere in Inner Mongolia:

Jade dragon of the Hongshan culture (4700 BC – 2900 BC) found in Ongniud, Chifeng

Fresco in the Liao dynasty (907–1125) tomb at Baoshan, Ar Horqin

Khitan people cooking. Fresco in the Liao dynasty (907–1125) tomb at Aohan

Maidari Juu temple fortress (美岱召; měidài zhào) built by Altan Khan in 1575 near Baotou

Da Zhao temple (also called Ikh Zuu) built by Altan Khan in 1579

Badekar Monastery (1749) near Baotou, Inner Mongolia. Called Badgar Zuu in Mongolian

Genghis Khan Mausoleum (1954)

One of China’s space vehicle launch facilities, Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center, is located in the extreme west of Inner Mongolia, in the Alxa League‘s Ejin Banner. It was founded in 1958, making it the PRC’s first launch facility. More Chinese launches have occurred at Jiuquan than anywhere else. As with all Chinese launch facilities, it is remote and generally closed to the public. It is named as such since Jiuquan is the nearest urban center, although Jiuquan is in the nearby province of Gansu. Many space vehicles have also made their touchdowns in Inner Mongolia. For example, the crew of Shenzhou 6 landed in Siziwang Banner, near Hohhot.

All of the above are under the authority of the autonomous region government. Institutions without full-time bachelor programs are not listed.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Inner Mongolia. |

Infectious and mysterious in character, it has concise yet elegant lyrics, euphonious melodies and diversified themes. It is Khoomei (Long-tune Song, Hooliin Chor, Throat Harmony or Throat Singing), the living fossil folk music of the Mongolian and one UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, which is teased by the Han Chinese as “The Wolf’s Cry ”.

Khoomei’s charm lies in its biphonic sound achieved through the tighten of throat and the manipulation of tongue, by the same person. What is more incredible is that both follow different rhythms. The result is that you can hear two voice sung from the same person at the same time, one is low and melodious, which forms the background music, while the other is penetrating and high-pitched, which has lyrics and is the highlight. From some sense, it is acrobatic performed through throat and tongue.

.jpg) |

| As we know, whenever the Mongolian holds a banquet, it will last for three days and nights. No banquet and party will be complete without Khoomei, and there are so many songs that you wont hear a repeated one during this period. |

By present, Khoomei prevails in Tuwa of Siberian, Mongolia, Russia, Altai of Xinjiang, Khakass and Inner Mongolia. In Gyuto and Gyume Monasteries of Tibet, lamas there also use throat voice to chant the prayers. For a Khoomei master, it is a piece of cake to sing their own ethnic songs, or the popular songs of the Han Chinese as well as any classic song of America and Europe.

“Khoomei” means “song of eternity”. It is a gem inspired by the spectacular grassland and the unrestrained nomadic lifestyle. Over one thousand years ago, the Mongolian’s ancestors migrated westward from the dense forests of Black Dragon River to Mongolian plateau, with lifestyle shifting from hunting to animal husbandry. During this process, Khoomei emerged. The following years saw it replaced the narrative hunting song (Short-tune song) as the dominating sight. Epitomizing the Mongolian’s culture, philosophy, customs and religion, Khoomei exerts profound and lasting influence on every aspect of their life. Today, it is a short-cut for us to unravel this nationality’s legacy and heritage. Khoomei is to the Mongolian just like Beijing opera is to the Han Chinese, the Kam Grand Choirs to the Dong people and Tibetan opera to the Tibetans. It has become a cultural identity and integral part of the Mongolian’s life. During Wedding Ceremony, holidays, religious festivals and especially the Naadam Festival, Khoomei is performed enthusiastically, which is one of the most eye-catching and expecting parts. As we know, whenever the Mongolian holds a banquet, it will last for three days and nights. No banquet and party will be complete without Khoomei, and there are so many songs that you wont hear a repeated one during this period.

.jpg) |

| This infectious and mysterious sound that resonates between heaven and earth may be straight-ford and imposing at first impression, but as long as you listen contently, you will be spellbound by its appealing tunes and indescribable charm. |

Dynamic and ever-changing in tune, Khoomei is profound in theme, which addresses almost all the elements typical of Inner Mongolia: the enticing landscape, the beautiful Mongolia ladies, the strong Mongolian men, their ancient heroes and vibrant daily labor life. The beauty of life, friendship and love are also eternal subjects. Judging from the different occasions it serves, Khoomei splits into Love Song, Departing Song, Homesick Song, Wine Toast Song, Banquet Song, War Song, Hunting Song, Warrior’s song and Mourning Song. Through Khoomei, the living environment and spirit world of the Mongolian are revived and revealed before us vividly.

According to a famous musician, Khoomei is a voice flows from the innermost corner of the Mongolian’s heart, a voice imbued with wisdom, philosophy and emotion. Hence, no matter you can understand the lyrics or not, this captivating music can tug your heartstring easily. The best way to enjoy Khoomei is to close your eyes and let the arresting song carry you away.

Khoomei has developed four variants in Inner Mongolian, with some intertwine with one another especially along the bordering area: Hulunbuire Khoomei, Xilingol Khoomei, Ordos Khoomei and Alxa Khoomei.

.jpg) |

| Khoomei in western Inner Mongolian mirrors the balance of simplicity, archaic and religion. It is the celestial voice for those who want to seek console and serenity in this far-flug getaway to nature. |

From east to west, the lush grassland gives way to hills and desolate deserts. In Hulunbuire and Horqin district, the eastern part of Inner Mongolian, the well-fed and happy nomads interpret Khoomei into a high-pitched, inspiring and passionate music with free form and concise lyrics. In Hulunbuire,the purity and sweetness of voice are valued, besides, the liberal use of ornamental vibrato bestows it with sumptuous beauty. Most Khoomei singers in Hulunbuir are women. Representatives songs include: The Expansive Grassland《辽阔的草原》. In Horqin, Khoomei is distinguished by its flowing, soothing and profound melody.

Moving westward, you can reach Xilingol, the political, economic and cultural center of Inner Mongolia since the 13th century. Xilingol has long been reputed an ideal pasture thanks to the mild weather and lush grass. Khoomei here adopts lingering melody, enlightening feeling, profound artistical effect, complete form and intricate structure. It is also notable for the broad range of voice, simplicity and sweet melancholy. Judging from tunes, lyrics, contents and artistic value, Xilingol Khoomei highlight the essence of Khoomei and become one of the top four representatives. Khoomei singers are mainly composed of men. Representative song include Little Yellow Horse《小黄马》.

Keeping advancing westward to Ordos and Alxa, you will notice the undulating grassland is replaced by barren landscape of Gobi and desserts. Life here is less colorful, so does Khoomei. With few ornamental vibrato, Khoomei here stays true to its original look and shows strong religious influence. Khoomei in Ordos has lively and dramatically-changing tunes, Khoomei in Alxa is calm, penetrating and overwhelming.

2017-11-23 22:50 GMT+8

2017-11-23 22:50 GMT+8

The capabilities of a human body are sometimes beyond a brain’s imagination.

For example, it’s hard for most people to believe the sound in the video above came from a human being rather than an instrument.

That is because the singer is able to produce a continuous bass and simultaneously produce one or more pitches through his/her throat.

That unique way of singing is known as khoomei, or hooliin chor (throat singing), an art of singing practiced by Mongolian communities in Inner Mongolia in northern China, Mongolia and the Russian republic of Tuva. It is also known as Tuvan throat singing in other cultures.

Through the throat singing band Alash’s performance in the video below, you may get a better idea of what this art form sounds like.

It is believed the Khoomei could be traced back to Huns, the nomadic people living between the 4th and 6th centuries in Central Asia and Eastern Europe.

Mongolians in ancient times imitated the sound of nature, such as waterfall, forest and animals, during nomadism and hunting as a way of connecting and showing respect to the nature.

This singing art was officially inscribed on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage by the UNESCO in 2009.

Photo via g-photography.net

Once endangered

Life styles keep changing. Khoomei, the art that was born in certain geography characteristics and production mode, was on the verge of extinction for a while in history since less people were able to perform.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that the art was flourished again along with the more frequent communications with neighboring countries.

57-year-old Hugejiletu, one of the most renowned inheritor of the intangible cultural heritage in China, wasn’t able to perform Khommei at all back in 1996.

Khoomei master Hugejiletu/Photo via China Youth Daily

When he traveled to Australia to perform traditional music and instrument for local audience, he was questioned by local reporter how come they didn’t bring Khoomei.

“There were so many of us, yet none could perform Khoomei. I felt ashamed that I couldn’t inherit the culture of my own people,” Hugejiletu told China Youth Daily in 2015.

At the age of 39, he embarked on a tough journey to learn this art. More Khoomei masters from different countries were also invited to Inner Mongolia to help re-boom the culture.

“As a Mongolian, it’s my responsibility to inherit and spread the music and art of our own people,” he said.

As the “living fossil” of Mongolian culture, Khoomei has drawn wide attention from international communities, including musicians, experts of sociology, anthropology and historians.

Khoomei’s charm lies in its biphonic sound achieved through the tighten of throat and the manipulation of tongue, by the same person. What is more incredible is that both follow different rhythms. The result is that you can hear two voice sung from the same person at the same time, one is low and melodious, which forms the background music, while the other is penetrating and high-pitched, which has lyrics and is the highlight. From some sense, it is acrobatic performed through throat and tongue.

.jpg) |

| As we know, whenever the Mongolian holds a banquet, it will last for three days and nights. No banquet and party will be complete without Khoomei, and there are so many songs that you wont hear a repeated one during this period. |

By present, Khoomei prevails in Tuwa of Siberian, Mongolia, Russia, Altai of Xinjiang, Khakass and Inner Mongolia. In Gyuto and Gyume Monasteries of Tibet, lamas there also use throat voice to chant the prayers. For a Khoomei master, it is a piece of cake to sing their own ethnic songs, or the popular songs of the Han Chinese as well as any classic song of America and Europe.

“Khoomei” means “song of eternity”. It is a gem inspired by the spectacular grassland and the unrestrained nomadic lifestyle. Over one thousand years ago, the Mongolian’s ancestors migrated westward from the dense forests of Black Dragon River to Mongolian plateau, with lifestyle shifting from hunting to animal husbandry. During this process, Khoomei emerged. The following years saw it replaced the narrative hunting song (Short-tune song) as the dominating sight. Epitomizing the Mongolian’s culture, philosophy, customs and religion, Khoomei exerts profound and lasting influence on every aspect of their life. Today, it is a short-cut for us to unravel this nationality’s legacy and heritage. Khoomei is to the Mongolian just like Beijing opera is to the Han Chinese, the Kam Grand Choirs to the Dong people andTibetan opera to the Tibetans. It has become a cultural identity and integral part of the Mongolian’s life. During Wedding Ceremony, holidays, religious festivals and especially theNaadam Festival, Khoomei is performed enthusiastically, which is one of the most eye-catching and expecting parts. As we know, whenever the Mongolian holds a banquet, it will last for three days and nights. No banquet and party will be complete without Khoomei, and there are so many songs that you wont hear a repeated one during this period.

.jpg) |

| This infectious and mysterious sound that resonates between heaven and earth may be straight-ford and imposing at first impression, but as long as you listen contently, you will be spellbound by its appealing tunes and indescribable charm. |

Dynamic and ever-changing in tune, Khoomei is profound in theme, which addresses almost all the elements typical of Inner Mongolia: the enticing landscape, the beautiful Mongolia ladies, the strong Mongolian men, their ancient heroes and vibrant daily labor life. The beauty of life, friendship and love are also eternal subjects. Judging from the different occasions it serves, Khoomei splits into Love Song, Departing Song, Homesick Song, Wine Toast Song, Banquet Song, War Song, Hunting Song, Warrior’s song and Mourning Song. Through Khoomei, the living environment and spirit world of the Mongolian are revived and revealed before us vividly.

According to a famous musician, Khoomei is a voice flows from the innermost corner of the Mongolian’s heart, a voice imbued with wisdom, philosophy and emotion. Hence, no matter you can understand the lyrics or not, this captivating music can tug your heartstring easily. The best way to enjoy Khoomei is to close your eyes and let the arresting song carry you away.

Khoomei has developed four variants in Inner Mongolian, with some intertwine with one another especially along the bordering area: Hulunbuire Khoomei, Xilingol Khoomei, Ordos Khoomei and Alxa Khoomei.

.jpg) |

| Khoomei in western Inner Mongolian mirrors the balance of simplicity, archaic and religion. It is the celestial voice for those who want to seek console and serenity in this far-flug getaway to nature. |

From east to west, the lush grassland gives way to hills and desolate deserts. In Hulunbuire and Horqin district, the eastern part of Inner Mongolian, the well-fed and happy nomads interpret Khoomei into a high-pitched, inspiring and passionate music with free form and concise lyrics. In Hulunbuire,the purity and sweetness of voice are valued, besides, the liberal use of ornamental vibrato bestows it with sumptuous beauty. Most Khoomei singers in Hulunbuir are women. Representatives songs include: The Expansive Grassland《辽阔的草原》. In Horqin, Khoomei is distinguished by its flowing, soothing and profound melody.

Moving westward, you can reach Xilingol, the political, economic and cultural center of Inner Mongolia since the 13th century. Xilingol has long been reputed an ideal pasture thanks to the mild weather and lush grass. Khoomei here adopts lingering melody, enlightening feeling, profound artistical effect, complete form and intricate structure. It is also notable for the broad range of voice, simplicity and sweet melancholy. Judging from tunes, lyrics, contents and artistic value, Xilingol Khoomei highlight the essence of Khoomei and become one of the top four representatives. Khoomei singers are mainly composed of men. Representative song include Little Yellow Horse《小黄马》.

Keeping advancing westward to Ordos and Alxa, you will notice the undulating grassland is replaced by barren landscape of Gobi and desserts. Life here is less colorful, so does Khoomei. With few ornamental vibrato, Khoomei here stays true to its original look and shows strong religious influence. Khoomei in Ordos has lively and dramatically-changing tunes, Khoomei in Alxa is calm, penetrating and overwhelming.

You can join our 5-Day Naadam Fair Tour in Inner Mongolia to listen to Khoomei, enjoy horse racing, wrestling and archery as well as to sample the delicious Inner Mongolia food.

You can join our 5-Day Naadam Fair Tour in Inner Mongolia to listen to Khoomei, enjoy horse racing, wrestling and archery as well as to sample the delicious Inner Mongolia food.